In 1996, Democratic President and amateur saxophonist Bill Clinton uttered the words, “the era of big government is over.” Later in 2008, Democratic President and current celebrity Barack Obama’s team met to try their darndest to solve the Great Recession… by bailing out the big banks of course. Prior to Clinton’s speech, in the late 70s and in the throes of recession and inflation himself, Democratic President and noted home builder Jimmy Carter began deregulating trucking, shipping, railroads, and appointed several key neoliberal economists to key positions in government (a subject for another post). While Republican Congressional majorities and presidents slash regulations, oversight, and cut taxes on the wealthy, Democrats do ~checks notes~ pretty much the same thing?

Now how the hell did we get in this mess?

There are many theories about why the Democratic Party, sometimes known as the “Party of the People,” got into this mess. One is that the high inflation and high unemployment in the late 70s (called “stagflation”) led President Carter to try new economic ideas in an attempt to solve the problem. Another is that a decades-long political battle by the wealthy bore fruit by eventually shifting politics away from regulating the rich to filling their pockets. An additional theory, which I find quite fun, is that the shift to neoliberal economics was just the rebellious young generation of politicians bucking their parents' political beliefs. So which is it? I’d argue there’s truth in all of these stories. There’s truth in others too. Regardless, in the mid to late 1970s, the party of the people shifted away from the working and middle class toward the affluent and well educated. Simultaneously, the Republicans continued their shift toward the ultra-rich. Though this does beg a question: what is neoliberalism? Among other things, it is defined as a belief that markets govern themselves, that the government should get out of the way, that tax cuts for the wealthy benefit everyone, and that global free trade is always a good idea.

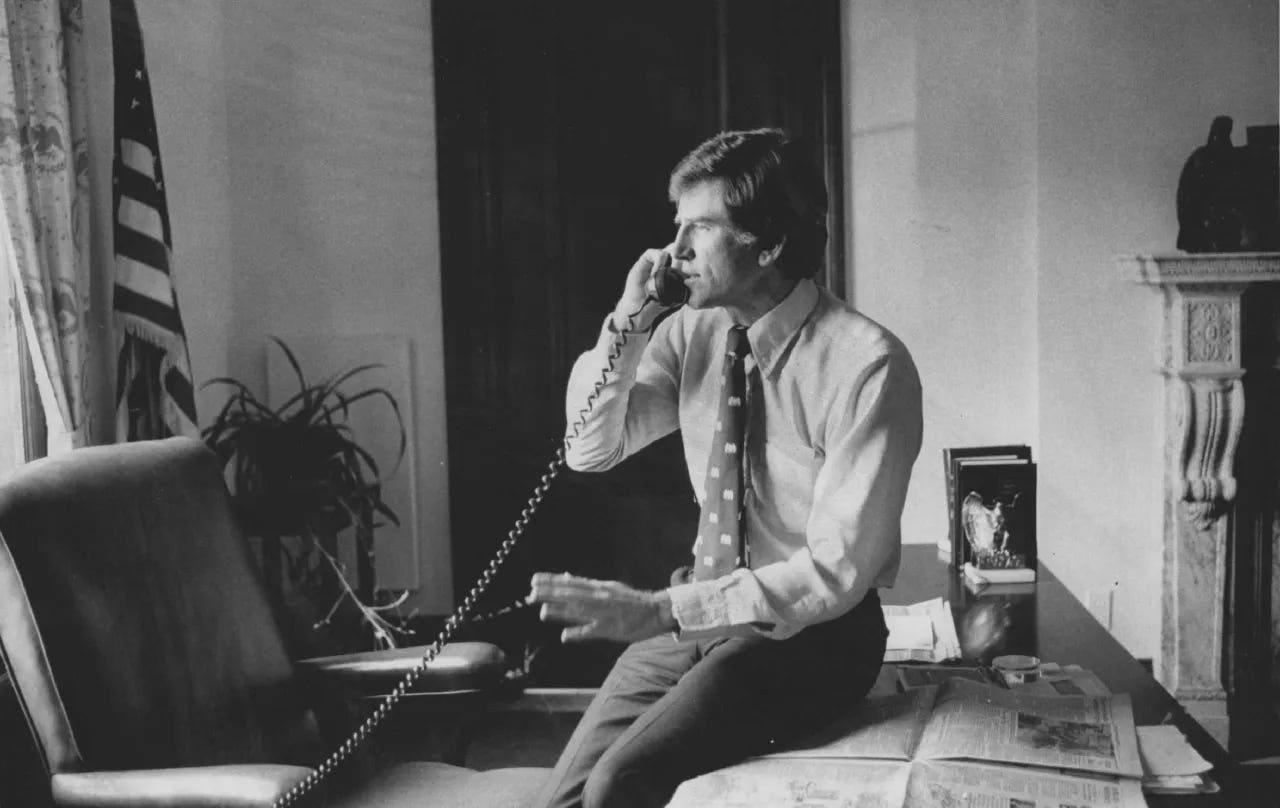

The party of the people became the party of tech innovation and college degrees. Many of the new Democratic leaders in that era (some names you’ll hear me say too often: Michael Dukakis, Gary Hart, Paul Volcker, Bill Clinton, Robert Rubin, Al Gore, Pete Stark, among others), referred to as the “Watergate Babies” due to being elected in backlash to Nixon’s famed scandal, had no interest in the politics of government regulation and oversight (like FDR and the New Deal). This generation wanted to get government out of the mucky economic oversight business and into supporting Wall Street, higher education, and the infant Silicon Valley. Jeremiads against big banks and wage thieves were no more. Instead, they stormed into office with soaring oratory against government corruption, slamming the “Nixon-thugs” and out-of-touch “Eleanor Roosevelt Democrats” alike. Gary Hart, one of the first of this generation to call himself an “Atari Democrat” (after his prioritization of tech innovation), called his stump speech “The End of the New Deal.” Hart was a pioneer of the Democratic candidate of the suburbs and the “managerial class.” This generation of Democrats emphasized tech, entrepreneurship, environmentalism, and deregulation. John F. Kennedy was their hero and Franklin Roosevelt was the decrepit past. Just as the Republican Party increased its shift towards deregulation, big business, budget cutting, and the ultra-rich, these new Democrats swept into Washington. Some, like historian and cultural critic Thomas Frank, call these new Democrats of the affluent the “Limousine Liberals.”

Over time, as major election victories by economically corporatist Republicans continue, the Democrats solidify these positions. With very few exceptions, Democrats in the 80s campaign as warriors against corruption, government waste, and overreach. In the 90s, President Clinton governed as a continuation of these beliefs. Under Clinton, as under Reagan, the tech industry escaped oversight, monopolies rose from the ashes of their previous defeats, the housing industry was deregulated (later an important event), and wealth inequality rose tremendously. Still, as the 80s and 90s marched on in neoliberal fashion, this deregulatory shift wasn’t enough for many of America’s industries. “Ideally,” famed General Electric CEO Jack Welch once said, “you’d have every plant you own on a barge.” What better way to avoid pesky oversight? Bill Clinton’s “New Democrats” (the ambitious successor of the Atari Dems) sought to marry the right-wing libertarian think tank with the liberal professoriat. He stormed into office with soaring oratory proclaiming America’s great multicultural democracy and diversity and paired it with a commitment to achieve the best of this diverse democracy through cutting welfare and spurring tech innovation. The Baby’s Boomers’ protest mottos of the 60s and the anti-oversight neoliberalism of the 70s and 80s, marching forward together into the next great American century. I’m sure that went well.

There is no easy answer as to why these changes occurred in the Democratic Party. The reality is that, for decades, the Democratic Party has come to see itself (and be seen by voters) as the party of the Ivy League professor and the tech entrepreneur. Campaign messaging aside, Democratic candidates have long seemed to lose their passion for cracking down on corrupt CEOs and fighting for economic freedom and stability. In the words of Thomas Frank (from whom the title and subtitle for this article are respectfully stolen), “inequality is the reason that some people find such significance and meaning in the ceiling height of an entrance foyer or the hop content of a beer, while other people will never believe in anything again.” Perhaps meaning, believing in something, is less about fancy words and Ataris than it is about community, financial stability, and true hope for the future.